HTML Essentials in Easy Steps

Code Institute and Mike McGrath

Validate your HTML code against standard rules

Many HTML tags need to be opened and closed.

Between the <html> tags add all the other (child) elements.

Fill in the Blanks with Placeholder Text

Nest an Anchor Element within a Paragraph

Make Dead Link Using the Hash Symbol

The checkbox Type input Element

The select/optgroup/option Elements

The details and summary Elements

description, keywords and author Metadata Types

Test your page on different simulated screen sizes:

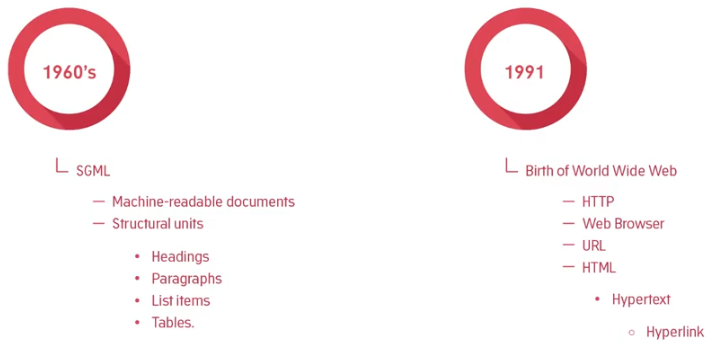

Now before we get into the details of the hypertext markup language, HTML. Let's take a look at how HTML came about and why it has changed the world in a very real way.

In the 1960s, three employees in IBM created the general markup language, GML. Its purpose was to enable the sharing of machine readable large project documents in government, law, and industry. Machine readable means that it could be understood by a computer. Now the GML, later standardized as the SGML, allowed electronic documents to be arranged into structural units such as headings, paragraphs, list items, and tables. But what the SGML did not include was hypertext.

Fast forward a couple of decades, in the late 1980s and still today, the European laboratory for particle physics in Geneva, known as CERN, was a meeting place for physicists from all over the world where highly abstract and conceptual thinkers engage in the contemplation of complex atomic phenomena, that occur on a minuscule scale in time and space. The results of such thinking produced research projects. Often, there was overlap between project ideas, breakthroughs in one area of research could potentially accelerate progress in another. Research was also undertaken in collaboration with institutes all over the world. And these research projects needed to be documented. Further, the documents needed to be shared.

A certain employee by the name of Tim Berners-Lee was working in one of the computing services sections at that time. And he had the idea of enabling researchers from remote sites across the world to organize and pull together information. But instead of simply making available a vast number of research documents as files that can be downloaded to individual computers. He suggested that you could actually link the text in the files themselves, in other words, there could be cross references from one research paper to another. This would mean that while reading one research paper you could quickly display part of another paper that contained directly relevant text or diagrams. Documentation of a scientific and mathematical nature would be represented as a web of information held in electronic form on computers across the world. Berners-Lee thought this could be done by using some form of

hypertext, some way of linking documents together by using buttons or links on the screen, which he just clicked on to jump from one paper to another.

As it happened, Tim had been working on his own document and text processing project called Inquirer since 1980. Now the concept of hypertext had been around since the 1940s and early Apple computers and applications that had applications that could link documents together. But only on the same machine, you couldn't link across a network. Figuring out how to make jumps to computers on the other side of the world had yet to be cracked.

But in 1991, Berners-Lee demonstrated a basic but attractive way of publishing text by developing some software himself and also developing his own simple network protocol. By the way a protocol is a set of rules for communicating between computers across a network. This protocol allowed for retrieving other documents via the hypertext links. The protocol known as HTTP stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol. The text form format for traveling along HTTP was named HTML which stood for the Hypertext Markup Language, term hypertext.

HTML was based on the SGML and consisted of just a few tags or elements. These tags are special characters added to an electronic document that designates some of the same structural units as the HTML but in addition to the SGML, HTML had included a hyperlink tag. Berners-Lee also built the very first web browser to receive and display those link documents. To receive a document you needed the address of the computer where that document was stored, along with the name of the document, this became known as what was called the URL, the Uniform

Resource Locator. Software running on the URL location was called a web server. Now the web server listened for requests for a particular document, when a request came in the web server would return or serve the document back to the machine that had requested it. So the requesting machine was called the client and the serving machine was called the server.

Along with some others who recognized the potential of his work, Berners-Lee looked to magazine and print media for guidance as to what structural elements would be most useful for this project. And he kept things very simple, just a few tags were required to learn and add to a document. He also encouraged others to build upon his ideas and design further software for displaying HTML and also for setting up their own HTML documents ready for access. So the revolution had begun. Pretty soon other institutions began creating and linking these documents, and in doing so, the web of existing material out there on the internet grew. Hobbyists and universities got in on the act, a community group, people figured out how to display images on a web document, more tags were added to increase the structural features of a document. And within 5 years the web had exploded in size and complexity.

So let's look at the anatomy of a web page.

HTML uses elements to structure your content. These elements can be created in any text editor, that's the beauty of it. And you save your documents with a .html extension when saving, so that a browser will recognize them as such.

Browsers are coded to recognize the elements included in the document and will attempt to display the content as intended. The elements act as instructions to the browser, they say things like

And no matter how complex or sophisticated today's web applications are, at the heart of say Facebook and YouTube there lies this simple structure. Web documents will call them pages from now on, created in 1991 still work perfectly in the most modern of web browsers.

So what does an element look like? Well an element generally consists of an opening tag. Which is made up of some characters wrapped inside an angle brackets, as you can see here. The text to be structured known as the contents follows the back of the brackets and then it's completed with a closing tag which looks just like the opening tag but has a forward slash inside the angle brackets. In our example, we are shown an element that's used to

display text as something important, in a newspaper this would be a headline, in a research document this would be the title, as it would also be in a blog post.

So how does the browser know this? Well the browser is created to look for and recognize these tags. The tags act as instructions to the browser as to how to format the contents. The h1 characters inside the angular brackets of the opening tag say to the browser, until you're told otherwise all content after my right-hand angle bracket, is to be displayed in big bold text. The browser says ok and prepares to display the content as big and bold. As the browser reads the content from left to right it will eventually come across the closing tag. This closing tag says to the browser we're done here. No more big and bold text required in this element. The browser will continue scanning any other elements in the document until it sees a special closing tag. The closing tag is the special HTML tag with a forward slash in it. Then it will display or render the structural elements that are encountered during the scan.

Elements can contain text but they can also contain other elements. In the example shown here, we would say the paragraph element contains the emphasis element. Or we can say that the emphasis element is a child of the paragraph element. People refer to this as a child parent relationship or nested relationship. Any element that contains other elements is said to be the parent of those other elements. Those contained elements are called its children.

Now the elements form a tree structure like a family tree. The tree structure is called Document Object Model or DOM, for short.

Behind the scenes the browser sees all page elements as objects, and these objects have properties like font size, font family, background color, height, width, and much, much more. Languages like CSS, JavaScript, can access and manipulate these objects to create something dynamic and interactive. The paragraph element has two children. The first is the text, a paragraph, the second is an emphasis element, the emphasis element has one child. That is the text it contains.

A minimal HTML document can be created out of the fragment we've just seen by adding three necessary elements and a title. The first necessary element is called as the HTML element. This is the parent of all other elements.

We recognize this due to being the outermost element in the nested structure. The HTML element represents the document object in the DOM, it's the parent object of all the HTML elements on a page. The HTML element contains two necessary immediate children. Namely, the head element, and the body element. The body element generally contains tags that are used to lay content on the screen. But the head element contains tags that provide supporting information, such as the title of the page, and other links.

In our example shown here, the page title is displayed not in the main browser viewing window but in a browser tab. Links to resources such as externally hosted fonts that are used by the page are also often added as children of the

head element. Note though, that these links aren't clicked on to activate them, but the browser will automatically send a request to where they're located and add them to the page so they can be used.

The Markup Validation Service is a validator by the World Wide Web Consortium that allows Internet users to check HTML and XHTML documents for well-formed markup. Markup validation is an important step towards ensuring the technical quality of web pages.

This validator checks the markup validity of Web documents in HTML https://validator.w3.org/

Comments are used to highlight the purpose or function of some HTML structure.

It is a special set of characters that allow you to leave notes or instructions within your web document that is not seen in the browser. It represents textual notation within HTML markup. Comments are represented in HTML as content between <!-- and -->

<!-- This is a single line comment -->

Single line comments have their opening and closing tags on the same line as the text. When comments go over 2 or more lines, the industry standard is to place the comment tags on their own lines, above and below the text.

<!--

When we have more to say than can comfortably fit on one line, we use a multi-line comment.

The convention for a multi-line comment is to put the opening and closing tags of the

comment on their own lines above and below the text.

-->

Comments are important for documenting code and adding notes. They are not HTML elements and will not be visible on the web page.

So when should you use comments in your HTML? A useful approach is to add them to the opening and closing points of large nested chunks of code. That way, you know where the parent container begins and finishes.

Comments come in handy when modifying your HTML later, or when you are trying to find and fix errors (bugs). Commenting is particularly useful if you are trying to figure out what is causing an error in your code – as you can temporarily comment out (i.e. make dormant) the HTML elements. Then you can test your code in small sections to isolate the error.

Comments are essential for explaining to yourself - and any other developers who will work with the code - why you have done certain things. It will save you and your future teammates a lot of time if you leave an easy to understand comment with the code you wrote explaining what it does.

Combining HTML with CSS and JavaScript allows you to produce content that is only limited by your imagination! You can add elements such as images, text, links, forms, video and much more.

Web development is based upon three main coding languages: HTML, CSS and JavaScript

Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) – HTML is a language that specifies the structure of a webpage. HTML documents are plain text documents structured with elements. Elements are surrounded by matching opening and closing tags, and each tag begins and ends with angle brackets < >. HTML is the structure of the Web.

Cascading Stylesheets (CSS) – CSS is a language used to add styling to web pages. It allows you to alter the font, colour, size, and spacing of your content, split it into multiple columns, or add animations and other decorative features. CSS is the look of the Web.

JavaScript – JavaScript is a language that allows you to add interactivity to web pages. For example, JavaScript is used to display timely content updates, interactive maps, animated 2D/3D graphics, or scrolling video jukeboxes. JavaScript is the logic of the Web.

HTML is solely made up of elements and their attributes. That’s it. Nothing more. For now, think of elements as words wrapped in < > brackets that tell the browser how to display content.

Every HTML element consists of tags. There are two types of tags: An opening tag is written using less-than and greater-than brackets that wrap around the element type like this: <element_type>. An opening tag defines the beginning of the element and can have HTML attributes such as href or style. You'll become very familiar with HTML attributes as you go through this module.

A closing tag represents the end of the element. The closing tag is identical to the opening tag except for the inclusion of a forward slash immediately after the opening bracket </element_type>.

A closing tag cannot have attributes. If the element has content, its opening tag has to be closed. The content of the element is written between the opening and closing tag, and it is this part of the element that will be displayed on the web page. Not all tags need to be closed. Some that don't have any content are known as self-closing tags. We'll talk about those later.

When an element is nested inside another element, its opening and closing tags are indented with an extra tab to the right than the containing elements’ tags. Indenting your html elements this way makes it much easier to visualize where elements open and close because when an element’s opening and closing tags are on separate lines, they should always be indented by the same amount of tabs. Meaning the opening and closing tags should be directly above and below each other.

Mixing up the order of opening and closing tags can cause many issues with the layout of your page, especially when you start working with CSS. Getting into the habit of indenting your elements in this early stage of learning to code will make it much easier to spot when you have made a mistake later on.

An element defines the structure and content of the web page. As we explained earlier, most HTML elements consist of an opening tag, content, and a closing tag. However, some elements are self-closing because they can't hold any content.

Examples of self-closing tags are <img>, which is an element to display an image and cannot also contain text, <br> which provides a line break in text elements, and <hr> which creates a horizontal line for a topic break.

Self-closing elements only have one tag, as they can't contain any other elements there is no need to close them later in the code. You will sometimes see a forward slash at the end of this tag like this: <img/>. This forward slash was needed in earlier versions of html, though it is redundant in html5.

All elements have what are called attributes, and the attributes are always contained in the opening tag. Attributes are additional properties of an element. In the example below, you can see it uses an src attribute. This attribute supplies the image to be displayed.

<img src="picture.jpg">

HTML elements are usually either block-level elements or inline elements. A block-level element occupies the entire space of its parent element (container), thereby creating a block. Browsers typically display the block-level element with a new line both before and after the element. They have a rectangular structure. By default, these elements will span the entire width of its parent element, so it won't allow any other element to occupy the same horizontal space as itself.

The first thing in every HTML document should be the <!DOCTYPE html> declaration, because it tells the browser the version of HTML to expect in the current document. In this case, HTML version 5 (abbreviated to HTML5) is used. It is not an HTML tag, but it is placed above the opening HTML tag as the first thing included in the HTML file. A page can have only one DOCTYPE declaration. When you view the page in a browser, the declaration is not visible.

All HTML files need to follow the same basic structure: this consists of a <!DOCTYPE html> declaration and the primary elements. The first of these is the <html> element. Nested inside the html element are the <head> and <body> elements. Each of these primary elements, as well as the declaration, can be used only once per page. Take a close look at the image that demonstrates their structure.

All HTML documents are plain text files saved with the .html extension. They can be edited with any text editor and run in any browser.

As a rule, just remember that every HTML document has the HTML element at the outermost level, and in between the <html> and </html> tags is where the <head> and <body> elements go. In between the <body> and </body> tags is the body of the HTML ... that's where everything else will go: images, text, videos, anything you can imagine!

Let's look at some common HTML events.

There are three necessary elements namely HTML, body, and head, that can be only used once in a page. That's because they provide the base structure, but most other elements can be used multiple times on a page and there are a few elements that show up in nearly every web page created. So let's take a look at some of them here.

The p element is one of the most common elements and as you might have guessed it defines a paragraph. As with print media a paragraph creates a line break below it to visually separate from other paragraphs. This is used to emphasize a semantic separation of content. The same structure is used in a novel or a magazine.

Elements that create spacing below themselves are called block elements. Block elements appear vertically down the left-hand side of a page, at least until they're styled by CSS.

Paragraphs and headings work in concert to create the majority of the text content of a web page and its structure.

Now HTML has six heading elements which are numbered 1 through 6. H1 is the most significant and usually contains the title of the content, not to be confused with the title that appears in the browser tab, I mentioned earlier.

H2 represents a subsection, H3 and so on represent identifiers of further subsections until we get to H6.

Headings are also block elements.

Inline elements are elements that don't cause a line break below their display. Take the examples shown, there's an emphasis tag and a strong tag for italicizing or emphasizing and making something bold. Now the reason why they

don't introduce a line break below, is that you may want to emphasize or make bold some text within a paragraph in order to stress particular words or phrases. And you'll most often not want to add a line break below the stressed text. Just as you wouldn't when writing a regular document in Microsoft Word or similar.

Element start tags can also have attributes. An attribute is composed of the attribute name, optionally followed by a value.Now an attribute is used to select between different options of an element function or to provide extra information about what that element does. Take examples of attributes, like in element <link rel="stylesheet" href="stylesheet.css">. In this case, the attributes are rel and href, and their values are in quotes after the = signs. We'll see later how CSS targets these attributes in order to style the elements.

Some elements need to have at least one attribute to be of any use. The famous hyperlink element, also known as the a element (anchor), has an attribute that contains the address of the HTML resource that it links to. In HTML content links that are supposed to be interacted with you are the anchor elements. The anchor element defines an anchor or a specific part of a page that can be linked to and a link article somewhere so it needs an address.

So to use the anchor element as a link to another page we use the href attribute, which will hold the address of where it needs to go to. The href attribute has as its value the location of the page or resource we'd like to link to. In the example shown here, the link when clicked, will take us to google.com and in particular Google's default or home page.

The img element is used to define an image on a page. We use the source attribute to link to an image either on our server or somewhere else on the web.

The image also has an alt attribute. It's also considered best practice to include an alt attribute value on any images you use, because the alt attribute will display any text within the attribute, if the image doesn't load or if a vision impaired user is using a screen reader to visit your site. The screen reader will read the alt tag so put a description of the image you're adding in this attribute.

Another common textual feature is a list. Lists can be divided into two types, ordered and unordered. Unordered list displays as bullet points, the order of the bullet points is deemed unimportant. An example might be a list of ingredients in a recipe.

If the order of list items is important then we use an ordered list. By default the ordered list will display in numerical order with the first item numbered 1, second 2, and so on. But these can be customized to use letters or even Roman numerals. An example of the use of an ordered list might be the preparation of the steps required for the recipe.

Lists can also be nested within each other. Nested lists are good match for the sections and subsections of a

website.

Neutral elements such as a div and a span are also included. Not everything can be marked up as semantically as a paragraph or as emphasized text. Sometimes an element is needed to group other elements or to allow other information to be attached to a part of a document.

Div and span are intentionally, semantically neutral. That is they don't mean anything in themselves other than helping to identify structural areas on a page, but they can be given meaning through the use of CSS, which we'll see later.

In the image here, we open the <html> directly beneath the <!DOCTYPE html> declaration. We close the html element at the very end of the page by repeating the tag, but this time with a / before the tag name, like this: </html> This tells the browser that the element is closed and, in the case of </html>, that we are at the end of the web page.

The html element can have a lang attribute. This attribute is used to identify the language of text content on the web document using this syntax: lang="en-US". The lang attribute tells the browser which language the page is written in. English, for example, has the ISO language code en and if you want to be specific on what dialect of English is used you can append a county code such as en-US for American English.

When writing HTML code, it is always a good idea to create your closing tag immediately after creating your opening tag. That way you won’t forget to do it later. Many code editors will add it automatically for you

The <html> element tells the browser that the current document is a HTML document. This element contains the entire web page. It’s a container for all the other elements and is defined by its opening <html> and closing </html> tags. The html element is also known as the root element. This element has two directly contained (child) elements namely; <head> and <body>.

You’ll see as you move through the course that concepts like containment and parent/child, ancestor/descendant relationships play a big part in how HTML is structured. But for now just notice that the outermost tag <html> and its closing counterpart </html> contain (are placed outside) all the other html elements.

The <head> element contains metadata about the page and links to external resources such as Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and JavaScript files. This element is the first child of the <html> element. It holds all the information about the page that is not displayed in the browser.

Metadata – is data that describes other data. For example, it can specify who wrote the document, and provide a list of keywords and phrases used in the document. We will discuss metadata in more detail in a later section of this module.

The <title> element is contained (nested) inside the <head> element. It displays the document title. This title will appear in the browser tab rather than on the main browser window. Nothing listed within the <head> element directly appears on the main browser screen.

The purpose of the <title> element is to identify your page within a bunch of other browser tabs. The Repl.it live code editor won’t display the title for us, so take a look at the next image to see what a typical title looks like in a web browser. You can see that the title "My Web Site" appears in the browser tab.

The <body> element uses any local or external CSS and JavaScript included in the <head> element to apply logic and styling to itself and its contents. Any visible web page content is created within the opening and closing <body> tags. The <body> element is the only sibling of the <head> so it is also a first descendant of the <html> element. It's created immediately below the <head> element.

The <body> element contains the visible parts of the web document (page). Everything that a user sees on the page lives inside the <body>. Therefore, all of the page's content will be added within the <body> tags.

Content can include images, paragraphs, headings, links, forms, tables, lists. We'll get to play with all of these as we go through the course.

In this section, we will look at HTML elements for text.

Text is an integral part of any website and while we could write our text directly into the body element like this. And have it appear on the screen, as you can see it appears as one big block of text with no structure making it extremely hard to read. Fortunately, there are HTML elements we can use to structure the text on our web pages into headings and paragraphs. The text on a web page needs structure to be readable. Headings provide signposts to different topics and sections of the content on the page. Users can scan headings to find what they're looking for quickly and text broken up into paragraphs is easier to read. There are six heading elements to choose from. Each starting with an H, and numbered 1 to 6. The heading levels decrease in size and importance, heading tags have a top-down hierarchy from h1 to h6. They establish a hierarchy of importance starting from the largest h1, and on down through h2, h3, h4, h5, to the smallest h6.

The most commonly used HTML element for text is the paragraph element which represents a paragraph of text. It can be used to break up large amounts of content into smaller, more readable sections. By default, the content of a paragraph element will always start on a new line with a space above and below it.

Using headings and paragraphs together we can begin to structure the content of a webpage in a readable and usable way such as the structure of a blog post or newspaper article.

The headings on a web page have the same role as headings in a newspaper. Along with images, headings are the first elements noticed on a web page. There are six different headings in HTML.

Heading tags have a top-down hierarchy from <h1> to <h6>. They establish a hierarchy of importance, starting from the largest <h1> and on down <h2> <h3> <h4> <h5> to the smallest <h6>.

Headings are bold text by default. There should be only one <h1> element per page, while other headings can be used multiple times per page. They should follow the hierarchy of importance. Headings should be used semantically and should not be used to make the text bigger or bolder.

Heading levels should not be skipped. That means that a web page should include a <h3> element only if a <h2> element has also been used. Consequently <h3> should also not be used on the web page before a <h2> was used.

Heading elements change the size of their text content, with <h1> being the largest font and <h6> being the smallest. Headings not only give a web page a visual structure, but they create a programmatic structure too - allowing screen-readers for visually impaired users an easy way to scan the sections of a page. Search engines like Google give the text contained within headings more weight when looking for relevant search results, so they are also important for Search Engine Optimization (SEO).

Use a paragraph to:

The <p> element represents a paragraph of text. The text is easier to understand when it is split up into units. For example, a book may have chapters with headings. Under each heading, there will be one or more paragraphs.

Paragraphs are represented in web browsers as blocks of text that are separated from adjacent blocks by a blank space. Paragraphs are block-level elements. A block-level element occupies the entire space of its parent container, thereby creating a "block." By default, block-level elements begin on new lines.

If you want to start a new line within a paragraph element, you can use the <br> tag, which represents a line break in your text content. The <br> tag is a self-closing tag because it cannot contain any content. Therefore it does not have a closing tag.

Web developers traditionally use lorem ipsum text as placeholder text. The lorem ipsum text is randomly scraped from a famous passage by Cicero of Ancient Rome. Lorem ipsum text has been used as placeholder text by typesetters since the 16th century, and this tradition continues on the web. Well, 5 centuries is long enough.

Here is a web page to generate this type of text https://www.lipsum.com/

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut nec pellentesque est. Curabitur lacinia rutrum massa, vitae porta turpis convallis non. Proin maximus neque non tellus hendrerit, cursus porttitor turpis malesuada. Integer non maximus lacus. Nulla enim est, feugiat ac elit vitae, euismod placerat ex. Nulla luctus velit ac augue ultrices, nec accumsan nulla facilisis. Proin a pharetra risus. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Donec quis eros viverra, egestas lorem et, gravida magna. Quisque vel erat urna. Aenean a commodo eros, at commodo tellus.</p>

HTML can apply meaning to elements in the way that both the end-user and the browser can understand. For example, h1 represents a document heading. The P element represents a paragraph of text. As a result, these elements have a semantic aspect to them. Semantically subjective elements were developed even further with HTML5 which is currently the newest version of HTML.

Semantic HTML elements make it easier for search engines like Google to distinguish key information in headings or in the main content for their search results. Semantic HTML also provides additional functionality for the user and greater accessibility for users with impairments such as those who use screen readers to access the web. For now the important thing to remember about semantic HTML elements is that they are used to add meaning to content.

However, there are many times when we need to use HTML elements to control the structure of our content on the page where no semantic meaning is needed. Thankfully, there are two elements in particular called div and span that apply no direct meaning to their content.

A div element is what is called a block level element. Block level elements will spread the full width of the page by default. Meaning if you define two div elements one after another they will stack on top of each other. Div is short for division. A div divides the page vertically into sections.

A span element is what is known as an inline element. Inline elements only take up as much width as their content and they will share their horizontal space with other inline elements. Spans only move to a new line when there is no more room for them on the current line they are on. Like when typing a word document when the line of words reaches its maximum width next word typed moves to a new line.

Because <div> and <span> provide no context they are what are called semantically neutral elements. They are also known as structural elements. It means that they are used to represent divisions (div) or areas on a document’s layout. We can also specify areas (spans) within these divisions.

As div and span are structural elements they are used in combination with other elements so that both structure and semantic value can be provided in a webpage.

You've already seen heading and paragraph elements nested inside the body element; many other HTML elements can be nested inside one another too. Here we see spans nested inside divs. You can think of divs and spans as building blocks, a way to build a framework for the rest of your elements and content.

HTML can apply meaning to elements in a manner that both the end-user and the browser understand in a defined way. For example <h1> represents a document heading, <p> represents a paragraph of text. These elements have a semantic aspect to them. For example, <h1> can only contain text and displays the content in bold at a particular font size. These combine to highlight the reason for a document's existence. But <div> or <span> can contain any content and context.

By default, a <div> will not share horizontal space with another element. So when you place two in your code one after the other, they will each spread the full width of their container. Therefore they will stack one on top of the other.

As you become more comfortable with HTML, you'll find that a common pattern for designing web pages is using divs to layout their different sections. For example, you might have a <div> containing all your header content, a <div> containing all the main content, and a <div> containing all the footer content. The main itself could then be divided into different sections using nested divs which you could use to separate different portions logically.

The span element is a generic inline container for phrasing your text content. Like a <div>, a <span> doesn’t inherently represent anything, it's semantically neutral.

A <span> element is used for small chunks of text or other smaller parts of a page to group elements for styling purposes. <span> is an inline element, so it does not start on a new line, and it only takes up as much width and height as its content. Unlike <div> elements, you cannot change the width and height of <span> elements.

We can place any element beside a <span> element. Spans can be nested inside divs, but not vice versa. A Web page will not crash if a <div> is nested in a <span>, but it is bad practice to do so. Avoid putting block-level elements inside inline elements.

Now you have learned a little about HTML elements, it's time to introduce you to the other essential part of HTML, HTML attributes. HTML attributes are pieces of code that give an HTML element extra customizable properties beyond the standard ones that come with the element type itself. Attributes apply a vast range of different properties and behaviors to their elements depending on which ones are used and which values they're given. In this example, we have an anchor element that defines a clickable link and an image element nested inside it that can be clicked.

We will go into much more detail about these specific elements and their attributes in coming lessons but for now let's take a quick look at these attributes here and what they can do.

The anchor element here contains three attributes. The href is the URL the user will be taken to when they click on the link. The target controls the behavior of the link making it so that it is opened in a new tab. The title attribute shows the title text when the user hovers over the element with their mouse. The image element inside has a source attribute which tells the image element where to get the image file. And a height attribute controls the size of the image.

Here you can see the image has been loaded in the browser and if I hover over it with the mouse the “Click me!” title shows up. And if I click on the link it takes us to the URL provided and opens it in a new tab.

As you can see, HTML attributes add a huge range of new functionality to web pages. The syntax of a HTML attribute looks like this.

An attribute is made up of two parts: the name of the attribute is on the left, and the value of the attribute is on the right. Quotation marks surround the value of the attribute and an equal sign goes between the name of the attribute and its value.

We define attributes for a HTML element inside its opening HTML tag. They go after the name of the element and before the greater than sign that closes the opening tag.

A single HTML element can hold multiple attributes when you are defining more than one attribute. Each attribute name and value pair is separated with a space. If an attribute takes more than one value, then all the values for that attribute are wrapped in one pair of quotes and the values within it are separated with a space. This syntax and ordering of the code are essential so that the browser can read it and render what you're asking it to on the page. If something breaks in your code it's a good idea to check that you have the characters of your code in the right order and the spaces are where they need to be so that the program can read it. Tiny details matter a lot in code and with practice you'll become a pro at spotting the errors.

Each HTML element has specific attributes that will work with it; some HTML attributes must have particular attributes defined in order for them to work.

For example, an image element needs an attribute to tell it where to find the image file to display. During the following lessons, we will talk in detail about different HTML elements and their attributes. There's a lot to remember so I encourage you to make notes to help with your learning. Don't be afraid to Google specific elements and the attributes when you get stuck, even senior developers Google everyday. And practicing your researching skills is as important as learning the languages on this course.

class is a widely used HTML element attribute.

A class attribute provides a common identifier to multiple elements. The class attribute is mostly used to point to a style in a style sheet. (we'll get to styles later in the CSS module).

The class attribute is a space-separated list of the classes assigned to an element. Classes allow CSS and JavaScript to select and access specific elements. It enables elements to be semantically grouped together, and similar styles or actions can then be applied to them. Multiple elements with the same class value can be treated as a group for collective styling.

id is a widely used HTML element attribute. The id attribute provides a unique identifier for an element within an html document. Use an id to target a single element on a page with styling or other functionality.

While classes are intended to be reused on the page, an id attribute value must be unique. There should be only one element with each id value. For example, a web page should not have two elements with an id="paragraph".

Like classes, id attribute values are used to identify specific html elements. Other languages like CSS and JavaScript then use the id to attach other properties or behaviours to that element.

While you are unlikely to see any errors from your HTML code if you accidentally use the same id twice, it will cause issues when other languages try to use the id value. When these languages target an element by its id, they will only access the first one they find in the HTML.

Another thing to remember is that unlike the class attribute, we can't add multiple id values to the same element. An element can have one id, and that id must be unique.

One of the core elements of the world wide web is the <a> (anchor), also known as a hyperlink. Hyperlinks enable you to link source HTML pages to various destination pages/images, sections within the same page or websites. You need to click the links created on the source pages to reach the destination. The links can be in the form of text, images, or website addresses. Remember that HTML stands for hypertext markup language. Hypertext implies that it contains hyperlinks. Hyper means that order is not linear. The order of the linking does not matter and it is not important which document is visited first.

The <a> element can be used to link to other web documents files or locations within the same page. HTML links are defined by an anchor tag. To make text into a link you put the text you want to be clicked inside the anchor element between its opening and closing tags. The anchor element can also be wrapped around other elements so you can turn images, text headings, and many other elements into clickable links as well.

By default, an anchor element will turn any text inside it blue and an underline will appear when the element is hovered over with a mouse.

An anchor element must have a href attribute. HRef is short for Hypertext Reference and the value you give it is the location the user will be taken to when they click on the link. If the link you are providing in the href attribute is to a separate site, it is best practice to include the target attribute on your anchor element.

By default, the destination page always opens in the window of the source page itself. When you use the target attribute with its value set to "_blank", it changes the behavior of the link so that it opens in the new tab. Doing this means the user maintains a connection to the original website and they can open multiple links without having to use the browser back button to return to the source each time.

Each web page hyperlink is sensitive to three interactive states:

Style rules (see it later in CSS) can be used to emphasize each hyperlink state:

a:link { background:green;}

a:active { background:olive; }

a:hover { background:yellow;}

a:visited { background:aqua; }

<a href="https://stackoverflow.com" target="_blank" rel="help">Stack Overflow</a>

External links provide a link to another website page; this can be a link to another page on the same website or a link to another site. External links can also be used to download files.

Use the <a> element with a href attribute set to an external URL.

The target attribute on an anchor, when set to "_blank" ensures that the browser opens the link in a separate tab. It is essential to add target="_blank" when linking to a separate website from your own, as it prevents the user from being taken away from your website completely.

The rel attribute specifies the relationship between the current document and the linked document. Search engines may also use the information in the rel attribute to determine how to index or display the page. A rel attribute has many possible values, depending on the relationship that needs stating.

Common rel types are:

Take a look at this documentation for more information on rel types and their purposes.

Internal links (bookmarks) provide a link to an element within the same page. When clicked on it, the view of the page moves so that the relevant section is at the top of the browser window.

Internal link syntax looks like this:

<a href="#next-section">Jump to section on the same page</a>

The href attribute value has a # at the beginning, and the rest of its value relates to an id attribute value on an element somewhere else on the page. This link above looks for an element like shown below, with the id of "next-section" on it to jump to.

<div id="next-section"></div>

A hyperlink can also target a specific point in a different document using the document’s URL, followed by a # hash character, then the fragment identifier. For example, the tag <a href="index.html#top"> targets an element within a document named index.html that contains the unique fragment identifier name of top.

You can nest links within other text elements.

<p>

Here's a <a href="https://codeinstitute.net/">link to codeinstitute.net</a> for you to follow.

</p>

Is displayed like this: Here's a link to codeinstitute.net for you to follow.

Sometimes you want to add elements to your website before you know where they will link. This is also handy when you're changing the behavior of a link using JavaScript, which we'll learn about later. Set the href attribute value to a #, also known as a hash symbol, to create a dead link. The # character will ensure when the link is clicked, the current page is simply reloaded.

<p>Click here to view more <a href="#" target="_blank">photo gallery</a>.</p>

There are three ways to access the target of a hyperlink:

A designated character key is specified for a hyperlink by the accesskey attribute of an <a> anchor tag. The method to utilize the designated key generally requires the user to press ALT + accesskey with most web browsers, such as Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome, but it’s ALT + SHIFT + accesskey with Firefox.

As in everyday life HTML lists are handy, they can be used for to-do's, recipes, navigational links, and so on. They allow you to structure and group relevant information in an easy to read format. The most commonly used list types are ordered lists and unordered lists.

An ordered list is represented by the ol element. List item elements represented by the li element are nested one after another inside the ol element.

An ordered list is declared using the <ol> element, then each item in the list is defined using the <li> element, nested inside the <ol> element. Each list item contains a single item for the list, each displaying on its own line. By default, each list item will be numbered according to their appearance in the list. But you can override that by specifying character and roman numeral sequences using its type attribute. You can learn more about the different values you can apply to your ordered list in this documentation.

<ol type="A"> Alphabetically uppercase

<ol type="a"> Alphabetically lowercase

<ol type="I"> Order by roman numbers

An ordered list is used when the sequence of the list items is essential. It might reflect a sequence of steps to be carried out, or it might indicate some ranking of things. For example, when listing the steps in cooking a recipe.

You declare an unordered list using the <ul> element. Then just like with an ordered list, each item in the list is defined using the <li> element, nested inside the <ul> element.

By default, each list item will be displayed on a new line, with a bullet-point marker next to it. By default, the bullet point will be a solid circle. If the unordered list is nested inside another list, the bullet-point marker will change by default to reflect this. The type of bullet-point used can also be changed with CSS using the list-style-type property.

An unordered list is used when the sequence of the list items is not important. For example, a list of ingredients.

First of all - what is nesting? You have done lots of nesting of elements inside one another when writing your HTML code. The <body> is nested inside the <html> element, a <h1> is nested inside the <body> element etc. When nesting lists, we are simply nesting one list inside another one to create a sub-list.

Nesting lists are useful because nesting lists can create subcategories within a parent list item. Any type of list can be used for nesting.

A nested list should be wrapped in a list item. A nested list should relate to one specific list item, and one list item can have only one nested list. Take a look at the structure of the code in the example below.

A definition list is a unique type of list in which each list item has two parts – the first part being a term, and the second part being a description of the term in the first part. This is referred to as a name/value pair. For example, a definition name/value pair for the term “sun” could be “sun/the star at the center of our solar system”.

In HTML5, definition lists are created with <dl> </dl> tags, which provide a container for list items. Each list item term is contained between <dt> </dt> definition term tags, and each list item description is contained between <dd> </dd> definition description tags. The <dt> element alone does not indicate that its content is a term being defined – a nested <dfn> element must be used for that purpose. The <dfn> is used to indicate the term being defined within the context of a definition phrase or sentence.

Optionally, the </dt> and </dd> closing tags may be omitted – either form of <dt> and <dd> element is valid.

Each list item in a definition list can contain multiple <dt> and <dd> elements – to allow a single term to have multiple descriptions, or multiple terms to have a single description. Typically, browsers display the definition descriptions inset from their terms. Definition lists are also useful to contain a series of questions and related answers, or indeed any other groups of name/value data.

<dl>

<dt><dfn>Mouse</dfn></dt>

<dd class="grammar">noun</dd>

<dd class="spoken">[mous]</dd>

<dd>a small animal of various rodent families</dd>

<dd>a palm-sized button-operated device used to move a computer cursor</dd>

<dd>a quiet, timid person</dd>

</dl>

Tables are useful for structuring related information in an easily readable way. A table represents tabular data, that is information presented in a two-dimensional table composed of rows and columns of cells containing data. HTML tables are used to organize data or information in columns and rows. Tables can be used for anything from displaying Hospital patient data to cataloging Pokemon cards.

In HTML5, tables are created with <table> </table> tags, which provide a container for table rows. Each table row is created with <tr> </tr> tags, which provide a container for a line of table data cells. Each table data cell is created with <td> </td> tags, which enclose the actual data to be presented. Optionally, the </td> and </tr> closing tags may be omitted – either form of <td> and <tr> element is valid. A <table> element will typically contain numerous <tr> elements to create a table displaying multiple rows of data. Similarly, each <tr> element will typically contain numerous <td> elements to create a table of multiple columns of data. It is important to note, however, that each <tr> row in the table must contain the exact same number of <td> cells – so, for example, if the first <tr> row contains five <td> cells, all <tr> rows must contain five <td> cells.

The <caption> tag defines a table caption. It must be inserted immediately after the <table> tag.

The <thead> tag is used to group header content in an HTML table. The <thead> element is used in conjunction with the <tbody> and <tfoot> elements to specify each part of a table (header, body, footer).

Browsers can use these elements to enable scrolling of the table body independently of the header and footer. Also, when printing a large table that spans multiple pages, these elements can enable the table header and footer to be printed at the top and bottom of each page.

<table>

<caption>Scores</caption>

<thead>

<tr> <th>Season</th> <th>Goals</th> <th>Assists</th> </tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr> <th>2017-2018</th> <td>15</td> <td>33</td> </tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="3">2018-2019 - Injury</td>

</tr>

<tr> <th>2019-2020</th> <td>22</td> <td>34</td> </tr>

</tbody>

<tfoot>

<tr> <th>Totals</th> <td>37</td> <td>77</td> </tr>

</tfoot>

</table>

The HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the spine of the web. It allows for sending and receiving data. The communication includes a request and a response.

In HTTP there are two different roles: server and client. The Web browser is the client that can send requests to the server, asking for the information. The server answers (responds to) the client, transmitting the requested data.

The most common response (for now) is in the form of an HTML document and its contents. HTTP has several methods: GET, PUT, POST, DELETE

https://www.codeinstitute.net/

You might have noticed the http:// used in web addresses. This part of the address, called protocol, tells the browser to communicate across the internet using HTTP. In the above example, you can see the address uses https:// the s stands for secure. Therefore communication with the server is secure.

In this section, we're going to introduce you to creating forms with HTML.

Forms are one of the main points of interaction between a user and a website. They allow users to input and submit data via text fields and other controls to a server for processing. Forms have many uses from login and registration to secure websites, collecting customer feedback, buying products online, or booking events. A form is used anytime submission of user information is needed. A form contains input elements where a user can enter information such as an email address or password. There can be single line or multi-line text fields, drop down menus, check boxes, radio buttons, and many other elements utilized to collect data.

So what happens to the data input into a form? The browser uses HTTP to make a request to the server with this data and then the server responds. HTTP stands for the HyperText Transfer Protocol. And it is the spine of the web, it allows for sending and receiving data. The communication includes a request and a response. In HTTP there are two different roles: server and client. The web browser is the client that can send requests to the server asking for information. The server answers the client with a response transmitting the requested data. The most common response is in the form of a HTML document and its contents. HTTP has several methods; since we're talking about forms we're going to focus on the GET and POST methods.

The GET http method is the most straightforward. It is used whenever the user clicks on a link or types an address into the browser address bar. In the context of a form, the GET method uses the input from the user to send a request back. For example, when a user fills in a login form the server responds if the login details are correct or not. The GET method does not modify the data on the server side, it just receives it as it is. In other words, the GET method is read-only; it does not affect the data in any way.

The POST http method tells the server to accept and store the data. It is often used for submitting a file or uploading a form to a database. When this feedback form is submitted the data is posted to the database to be saved. So it requires a POST method to work.

In short, GET requests data from the server and POST pushes data to the server. In order to wire up our HTML forms correctly so that data can be both requested and pushed, our form and input elements need several important attributes which we will cover in the coming lessons.

A <form> element contains other elements that make up the structure of the form. Those elements can be text fields (single line or multiline), select boxes, buttons, checkboxes, radio buttons and many other elements used to collect data. In the following units, we will work through many of these and explain their properties.

An example of a common element you will see nested inside a <form> is an <input> element. An <input> element is a self-closing element; it does not have a closing tag. It can be set to accept different types of input using its type attribute. We will discuss this in more detail in the coming units. For now, here is an example of an input element that will accept text input:

<input type="text">

As the form element is for collecting data from the user, the form needs some important attributes to tell it where and how to send the data. To do this, we use the attributes action and method on the form element.

The value of the action attribute is the URL location of the data processing program to which the data will be sent or the next page to take us once the form is submitted..

The method attribute determines what type of HTTP method the form to take once it is submitted. Most common values:

<form method="POST" action="https://formdump.codeinstitute.net">

<input type="text"/>

<input type="submit"/>

</form>

As with all html attributes, the order that they are written in is not important. Most developers have a preference for the ordering they use, but there is no hard and fast rule for this. Therefore you will see occasions when a method attribute is defined before the action attribute on a form element, and vice versa.

The <label> element is used to add context to input fields, by providing a label for them. A <label> element has a for attribute, the value of which corresponds to the id of it's related <input> element.

For example this code: produces this output:

<label for="name">Name</label>

<input id="name" type="text">

You might be wondering why a <label> element would need to be connected to its corresponding <input> in this way, as surely it is obvious when looking at the form that the label and input field go together.

The reason that they are connected within the code is so that the screen readers for visually impaired users are able to direct their users to what content belongs in which field.

As we have already discussed, an <input> is an HTML element where a user can enter data. <input> fields have several important attributes that they need to function correctly. We have discussed the type attribute, including how it affects the display and behaviour of the input field.

As well as a type attribute, each input field must also have a name attribute. The name attribute is essential for processing the data the user has sent. It provides a key with which to pair the data in the database. For example, if a user inputs the data "William Preston" into an input field with name="full_name" on it, the data would be stored in the database as { "full_name" : "William Preston" }.

You will learn a lot more about storing and accessing data in the later modules of the course. The critical thing to remember for now is that without the name attribute, data from <input> can't be processed. It will not be sent when submitting the form.

An <input> field can have a placeholder attribute. The value set to the placeholder displays hint text before a user starts entering data into the field. When a user starts typing, the placeholder text will disappear.

An <input> field can also have a value attribute. This attribute specifies the initial value of the input field. This value will not disappear when a user starts typing, but they can delete and replace it if they want to. The value attribute is useful to pre-populate a form with existing data. When a value attribute is used on an input field with type="submit" the value given to the value attribute replaces the default "Submit" text on the button.

The <input> element can be one of many different types, depending on the value you give its type attribute. Each of these types collects a different type of data to store in a database. While many forms work correctly using text and password fields along with a submit button, you may at times need more sophisticated means of getting form input from your site users. Free text can be error-prone; typos are common. If you can help a user provide data in a way that is intuitive and reduces the risk of error, you will improve the user experience and minimise the risk of bad data being submitted. It can also control what the user is permitted to submit. Many of the input types listed below prohibit submission of the form if the user enters a value that is not permitted, and issue an error notice. Some also provide special controls that allow the user to easily select a permitted value.

Here are a few controls that can make life easier for you and more enjoyable for your users:

Take a look at this documentation for a full list of input types.

<input> elements can optionally include other attributes to control their performance:

It's important to make sure that features can be used across as many browsers as possible. To do this, visit the Can I Use? website. Type the feature into the search box, and it will display a list of compatible browsers and exceptions. For example, the search input type only appears with an X symbol on specific browsers and is a regular text input field on others. It's important to know what features are cross-browser compatible, especially if they are a significant part of your project.

A <textarea> is useful when you need to give the user an area to enter a more substantial amount of text than a simple <input type="text"> field provides. For example, in a contact form, a <textarea> would be used for writing the central part of the message.

Unlike the <input> element, the <textarea> element does have a closing tag. When you want to pre-populate your <textarea> with data, you put this between the opening and closing tags, instead of using a value attribute like you do for a <input type="text"> element.

The <textarea> element has two additional attributes: rows and cols. These attributes are used to set its size on the screen using numerical values.

The value given to rows sets the height of the text area, and the value given to cols sets the width.

Like the previous input types we have discussed, the <textarea> also needs values for name and id attributes, and its <label> element should have a matching for attribute for its id.

The <textarea> element can also take a placeholder attribute for hint text to be displayed in the text window before the user starts typing.

<label for="ta">Example textarea</label>

<textarea id="ta" name="comment" rows="10" columns="50" maxlength="250">

Some enclosed text as default content.

</textarea>

Optionally, it may also include a readonly attribute to prevent the user editing its content. – as its enclosed content is treated as its value.

An important thing to note, unlike a text <input> element, the <textarea> element has no value attribute, anything you put between the opening and closing textarea tags will be interpreted as values typed into the textarea field. So if you accidentally put a space between them, the browser will interpret this as a space entered into the textarea. This will cause any placeholder text you provided not to show.

HTML5 introduced new form elements that help organise content on the web page. One of them is <fieldset> which groups related elements by drawing a box around any elements nested inside it.

The <fieldset> element is usually followed by a <legend> element, which defines a title for the <fieldset> element. The legend content is displayed inside the top line of the fieldset border.

<fieldset>

<legend>Your details</legend>

<label>Name:<input type="text"></label><br>

<label>Email:<input type="email"></label>

</fieldset>

Checkboxes allow a user to choose multiple options from a list of options. They are input fields with the type attribute of checkbox.

<label for="accept_terms">Accept terms</label>

<input id="accept_terms" type="checkbox" name="accept_terms" value="yes" checked>

By default, the data sent to the server from a checkbox that is checked is the value of on. If you give the checkbox a value attribute, the value you give this attribute is the value that will be sent to the server.

In the example above, we've got a name attribute with the value of accept_terms, and a value attribute with the value of yes. When this is submitted, the data name/value pair sent to the server would be

{ "accept_terms" : "yes" }.

If the value attribute was omitted, the default value for the checkbox is on; the submitted data would be

{ "accept_terms" : "on" }.

A checkbox input element can have a checked attribute. This attribute does not need to fit the usual attribute_name="attribute_value" syntax. Simply adding checked inside the input element's opening tag is enough to make it work, as demonstrated in the example above. When a checkbox input has a checked attribute, the checkbox will be pre-checked when the form is loaded in the browser.

A checkbox input element needs a corresponding <label> element, so the user knows what the checkbox is for. When using a <label> with a checkbox, if you want the checkbox to appear to the left of the label, you will need to define the checkbox input element first and the label second. Each of your checkboxes can be nested within its own label element. By wrapping an input element inside of a label element it will automatically associate the checkbox input with the label element surrounding it.

All related checkbox inputs should have the same name attribute. Multiple checkboxes that share a common name can be visually grouped by surrounding their <input> elements by <fieldset> element. These may also contain <legend> element to state a common group name.

Here's an example of a preselected checkbox and a checkbox group:

<form>

<label>Yes, I would like to receive details <input type="checkbox" name="requestdetails" checked></label>

<fieldset>

<legend>Activities of Interest...</legend>

<label>Sailing <input type="checkbox" name="Do" value="Sail"></label><br>

<label>Walking <input type="checkbox" name="Do" value="Walk"></label><br>

<label>Driving <input type="checkbox" name="Do" value="Drive"></label><br>

<label>Ski-ing <input type="checkbox" name="Do" value="Ski"></label><br>

<label>Jogging <input type="checkbox" name="Do" value="Jog"></label><br>

</fieldset>

</form>

Radio buttons take their name from old-fashioned radios where if you pushed in one button the other buttons would pop out, allowing only one button to be pressed at any one time.

Radio buttons allow a user to choose only one option from a set of related options known as a radio group.

<input type="radio" name="payment_type" value="creditcard" checked>

<input type="radio" name="payment_type" value="paypal">

A radio group is defined by giving each of radio buttons in the group a name attribute with the same value. Once a radio group is established, selecting any radio button in that group automatically deselects any currently-selected radio button in the same group.

When a radio input has a checked attribute, the radio button will be pre-selected when the form is loaded in the browser.

Radio buttons also need a value attribute, the value of which is the data that is sent to the server. Only the selected radio button’s name/value data will be sent to the server:

{ "payment_type" : "creditcard" }.

When a button is selected, its switch is set to on and its name/value pair will be submitted, otherwise its switch is set to off and its name/value pair is not submitted. Unlike checkboxes, radio buttons that share a common name are mutually exclusive, so when one radio button is selected, all others in that group are automatically switched off.

Like a checkbox, an input field with a radio type attribute needs a corresponding label element, and if you want the radio button to be to the left of the label, it should be created first in the code.

Suppose there is a long list of related options available to a user. In that case, it is better from a User Experience and User Interface (UX/UI) point of view to use a dropdown list than using checkboxes or radio buttons. It is easier to comprehend one self-contained dropdown list than many checkboxes. A dropdown list takes up very little real-estate on the page until it's temporarily in focus (active). Dropdowns are also useful for mobile devices.

<form>

<label for="found">How did you hear about us?</label>

<select id="found" name="found">

<optgroup label="Media">

<option value="tv">TV</option>

<option value="radio">Web</option>

<option value="other">Other</option>

</optgroup>

<optgroup label="Web">

<option value="google">Google</option>

<option value="bing">Bing</option>

</optgroup>

</select>

</form>

You create a dropdown list with predefined options to choose from by using the <select> element. A select element must have a name attribute so that the data has an identifier to send to the database with the value selected.

The dropdown list with predefined options for the user to choose from contains one or more <option> elements. Each option contains a single choice for selection.

The <option> element displays the option text to be displayed and an optional value attribute that can act as a unique identifier for that option. If present, this value attribute will be sent to the server when the form is submitted. If the value attribute is missing, then the value will be taken from the text content of the option element.

An <option> element can have a Boolean attribute called selected. Like the checked attribute, this attribute does not conform to the usual attribute_name="attribute_value" syntax of most attributes. An option element with a selected attribute will be pre-selected and displayed by default when the page is loaded.

When an option has a selected attribute, it looks like this:

<option value="option value" selected>Option text</option>.

Optionally, the <option> elements may be grouped by enclosure in <optgroup> </optgroup> tags. The opening <optgroup> tag may specify an option group name via a label attribute.

A select option list will normally appear as a single-line dropdown list, unless a size attribute is included in the <select> tag to specify the number of rows to be visible.

A simple “autocomplete” feature can be provided for a text <input> using a <datalist> </datalist> element to enclose a number of predefined <option> values. The user may choose any one of the options, or type their own value into the input field directly.

A good example of when you will have seen this kind of functionality is in the search bar on Google. As soon as you start typing, Google starts suggesting things that might fit your search.

While not as complicated as google search, your datalist can provide a list of possible options that the user might select. The list can be seen right away when the input field is selected, and the list of options will change to autocomplete whatever the user is typing in, should any option from the datalist match the user input.

<form>

<datalist id="browsers">

<option value="chrome" >Chrome</option>

<option value="edge" >Edge</option>

<option value="firefox">Firefox</option>

</datalist>

<label for="browser">What browser do you use?</label>

<input type="text" id="browser" name="brower" list="browsers">

</form>

A datalist element must have an id. And this id value is then set to match a list attribute on an <input> field. The name attribute for your data goes on the <input> element. The value for each option is set using the value attribute on the <option>.

A form button is used primarily to submit the form data to the server. There are two types of elements that can do this:

An <input type="submit" value="SendInput"> element will create a submit button with the text of "SendInput" on it.

A <button type="submit" value="SendInput">SendButton</button> element will do exactly the same thing.

The difference between these two elements is that because a <button type="submit"> element has a closing tag, you can put other elements inside it, like spans, images or icons, for example. Whereas an <input type="submit"> button can only hold plain text as it's value.

Another type of form button attribute is the type="reset". This attribute can be applied to either an <input> or <button> element, and when clicked will reset the form to its original values when the page was first loaded.

Sometimes we need to prevent a user from submitting empty input fields. For example, we do not want to allow a user to sign up for a site if he/she did not enter an email or password. We need to validate these input fields. In other words, we need to make sure that they are not empty when submitting the form. We can achieve this with the required attribute. When it is applied, the user will be prompted to fill in all the required fields before they can submit the form.

The required attribute is another attribute that does not conform to the standard attribute_name="attribute_value" syntax, simply adding required to the input element's opening tag is enough to make that field required, like this:

<input type="email" required>

Adding a required attribute to the input field with the type="email" makes sure that field is not empty and that an invalid format of an email address cannot be submitted. It means that addresses without @ sign or the dot will not be submitted.

The required attribute can be added to any form input element: <input>, <textarea> and <select> can all have the required attribute applied. When applying the required attribute to <input type="radio">, the required attribute only needs to be applied to one of the input fields with the same name attribute on them. Then the form will be accepted when one radio option has been selected.

<form oninput="fn.value = firstname.value + ' ' + surname.value">

<input type="text" name="firstname">

<input type="text" name="surname">

<output name="fn"></output>

</form>

Within the <form> element use the following attributes to make form fields more accessible for those who can not use a mouse for navigation.

<form>

<input type="text" name="firstname" accesskey="f" tabindex="1">

<input type="text" name="surname" accesskey="s" tabindex="2">

<input type="email" name="email" accesskey="e" tabindex="3">

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

We already talked about the <img> element back when we were first introducing you to attributes. But let's go back over some of the details now you are more familiar with HTML syntax.

The <img> element is a self-closing element, meaning it cannot have other content nested inside it, and it has no closing tag.

<img src="daisys.png" alt="A close up photograph of daisys"/>

As you may remember from the attributes unit, the <img> element takes two important attributes: The src attribute, which takes the file path to the image file to be displayed. And the alt attribute for text to be displayed if the image file does not load, and to describe the image on screen readers for visually impaired users.

The <img> element can also take height and width attributes to control its size. Though it is worth bearing in mind, it is better practice to use CSS to control height and width properties..

By adding the title attribute to the <img> tag, the displayed picture gets a tooltip when the cursor hovers over it:

<img src="HTML5_Logo_64.png"

alt="HTML5 Logo"

title="HTML5 Logo">

Additional Perspectives From People We Like

“A picture is worth a thousand words”. When creating a web application, it can be hard to find images to illustrate your site. Some stock image websites have free downloadable images for websites. One of these is Pexels. When you download one of their images, you have an option to copy a link to it. Always use this link, for example in the alt attribute, as attribution for the image.

Sites you can source Free Stock Photography:

The <picture> element gives more flexibility to set image resources in your projects, as you can use it to set different images to be shown depending on the width of the browser viewport. By using the picture element, you can display different images to the user depending on the screen size they are viewing your webpage on. This is part of what is known as responsive design - changing how your website looks for mobile, tablet or desktop size screens.

The most common use of the <picture> element would be for art direction in responsive designs. Instead of having an image that is scaled up or down based on the width of the browser window, multiple images can be designed to fit nicely into the width of the screen.

<picture>

<source srcset="desk-small.jpg" media="(max-width:600px)">

<source srcset="desk-portrait.jpg" media="(max-width:800px)">

<img src="desk-landscape.jpg" alt="laptop, notepad and a mug on a wooden desk">

</picture>

The <picture> element holds two different elements: One or more <source> elements, and one <img> element.

When used with the <picture> element, the <source> element needs two important attributes: srcset, which defines the URL of the image to show. And media which accepts a media query.